1. Introduction

Twenty years ago, the founder of our firm, Duncan Glaholt, published a paper in the Construction Law Reports in which he advocated for the adoption of a prompt payment and adjudication system modelled on those in place in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and other jurisdictions.[1]

The argument was that the construction industry’s fundamental challenge at the time was the lack of timely, binding interim dispute resolution. Experience in other jurisdictions demonstrated that once this issue was addressed, payment and performance disputes were resolved at an early stage, significantly reducing the incidence of large-scale construction disputes. Mr. Glaholt argued that it was time for Canada to move away from its patchwork of after-the-fact remedies and dispute resolution practices and adopt minimum dispute resolution provisions grounded in adjudication principles successfully applied elsewhere in the world.

The idea slowly gained traction. Roughly ten years later, in February 2015, Bruce Reynolds and Sharon Vogel were appointed by the Ministry of the Attorney General and the Ministry of Economic Development, Employment and Infrastructure to conduct an expert review of Ontario’s Construction Lien Act. Their review culminated in a comprehensive 435-page report, published in 2017, which included 100 recommendations for legislative reform. Many of these recommendations were adopted by the legislature and integrated into the updated Construction Act in 2018 and 2019.

The most dramatic of those changes was, of course, the introduction of prompt payment and adjudication based on the UK model, with Ontario being the first Canadian jurisdiction to go that route.

Moreover, one of the key recommendations of the Reynolds & Vogel Report was for an independent review of the Construction Act to be conducted within five years of the new legislation’s enactment, with subsequent reviews every seven years thereafter.

The first of these independent reviews was completed by Duncan Glaholt. His report, 2024 Independent Review: Updating the Construction Act, was released on October 30, 2024. The report included 44 new recommendations for further reforms, with three major themes emerging: holdback, adjudication, and administration.

Coinciding with the release of Mr. Glaholt's report, Bill 216, Building Ontario For You Act (Budget Measures), 2024 went through its first reading on the same day. By November 6, 2024, Bill 216 passed its second and third readings and received Royal Assent. Most of the suggested reforms were implemented.

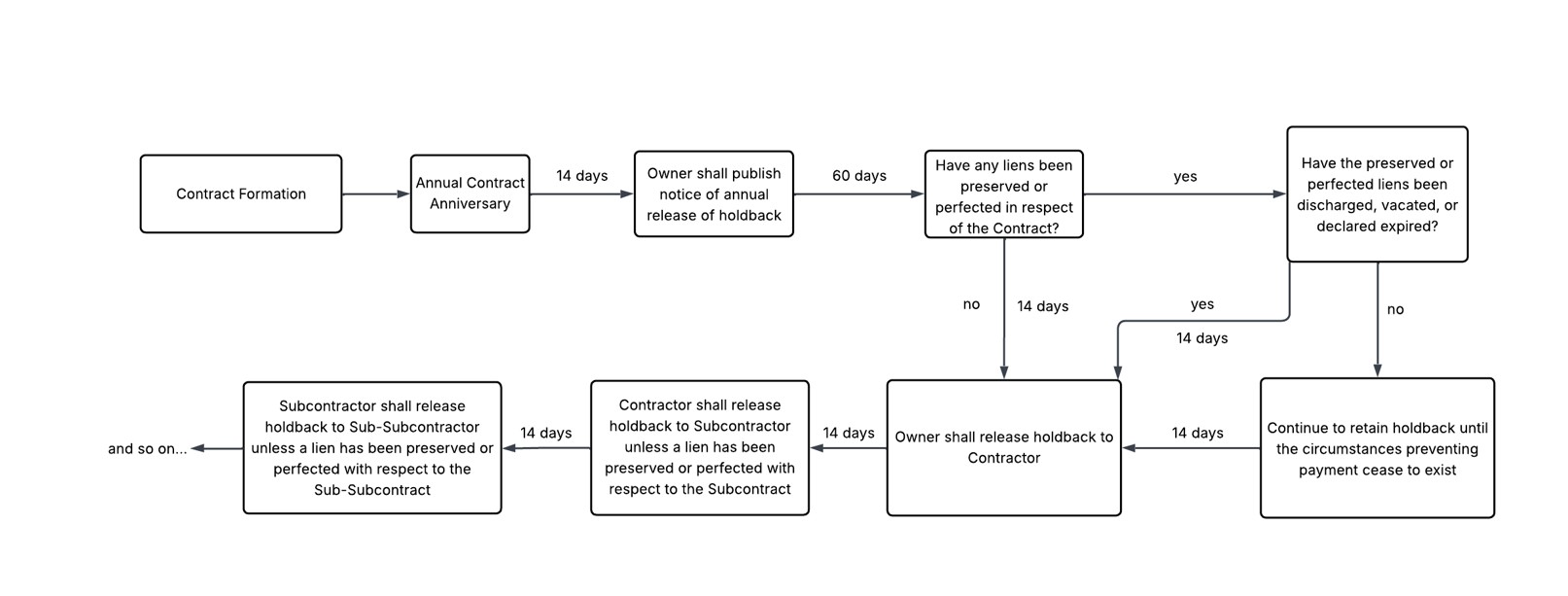

One of the most significant changes introduced through Bill 216 is the introduction of mandatory annual release of holdback whereby an owner has to make payment to a contractor of all the accrued holdback in respect of services or materials supplied by the contractor during the year immediately preceding the anniversary, unless a lien has been preserved or perfected and not discharged, vacated, or satisfied. Notices of annual release of holdback must be issued by owners in the prescribed form no later than 14 days after the anniversary date.

With respect to adjudication, significant changes include the ability for disputes to be determined by private adjudicators, giving parties greater flexibility in deciding how and by whom adjudications are conducted. The scope of adjudication has also been expanded and is now governed by Regulations rather than being explicitly set out in the Act.

Regarding the availability of adjudication, Bill 216 modified the availability of adjudication from being tied solely to “completion”, and provided that adjudications are available within 90 days after the date on which the contract is completed, abandoned or terminated, unless the parties to the adjudication agree otherwise.

More recently, on November 27, 2025, Bill 60, the Fighting Delays, Building Faster Act, received Royal Assent. Bill 60 introduces further amendments to the Construction Act, building on the changes previously introduced through Bill 216, the Building Ontario For You Act.

Bill 60 clarifies the rules governing holdback. Most notably, the annual release of holdback is no longer linked to lien expiry, as had been proposed under Bill 216. This change reflects concerns raised during the review process about the potential pitfalls of coupling annual holdback release to annual lien expiry, as discussed below.

The amendments introduced through Bills 216 and 60, including changes to holdback requirements for designers, proper invoices, prompt payment and adjudication, as well as other administrative updates, come into force on January 1, 2026, together with a new set of Regulations replacing the existing Ontario Regulation 306/18 and amending some other Regulations existing under the Act.

The recommendations from Mr. Glaholt and the legislative amendments in Bills 216 and 60 demonstrate an ongoing effort to streamline and modernize Ontario’s Construction Act.

Below is a summary of those changes.

2. Liens and Holdback

2.1 Mandatory Annual Release of Holdback

Under the pre-2026 version of the Construction Act, annual or phased holdback release was permitted only if the contract specifically provides for it and if the contract price is at least $10,000,000. This framework often left subcontractors and suppliers, who were typically most in need of regular or phased holdback release, dependent on the discretion of owners and contractors. Bill 216 repeals the provisions permitting optional annual release (section 26.1) and phased release (section 26.2) and establishes a scheme for mandatory annual release.

Under the new section 26, owners are required to publish a notice of annual release of holdback in the prescribed form 14 days following the anniversary of the effective date of the contract. The notice of annual release must specify the amount the owner intends to pay, and the intended payment date.

Bill 60 requires that the holdback be released no earlier than 60 days and no later than 74 days after the notice of annual release of holdback is published. In other words, the owner must release all holdback accrued during the previous year to the contractor, unless a lien has been preserved or perfected and has not been discharged, vacated, or declared expired.

Where a lien has been preserved or perfected and has not been discharged, vacated, or declared expired, new subsection 26(7) requires the payer to release the holdback no later than 14 days after the circumstances preventing payment cease to apply. In practical terms, once the lien is discharged, vacated, or declared expired, the 14-day period for release of the holdback re-commences, provided that it is not earlier than 60 days after publication of the notice of annual release of holdback.

Once a contractor receives its holdback, it must pay all accrued holdback to its subcontractors within 14 days, unless a lien has been preserved or perfected in relation to the subcontract. Similarly, subcontractors must pay sub-subcontractors within 14 days of receiving their holdback, unless a lien has been preserved or perfected in related to the sub-subcontract, and this obligation continues down the contracting chain.

Below is a visual representation of how this works:

2.2. Restrictions on Withholding Holdback

Bills 216 and 60 introduce new restrictions on a payer’s ability to withhold payment of holdback from contractors and subcontractors when it has become due.

Bill 216 removes the notice of non-payment of holdback from the statutory framework. Under the pre-2026 version of the Construction Act, section 27.1 allowed owners, contractors, or subcontractors to withhold all or part of the holdback if they issued a notice of non-payment by the prescribed deadline. Section 27.1 has now been fully repealed, and notices of non-payment have been eliminated from the Construction Act. As a result, holdback must be paid annually without any deduction, set off, or withholding.

Bill 60 also amends the scope of section 30. Under the pre-2026 version of the Construction Act, payers were prohibited from setting off retained holdback, using it to pay for replacement work, or satisfying claims against a defaulting party until all lien rights related to the holdback have expired, been satisfied, discharged, or otherwise addressed. The new section 30 expands these restrictions by also prohibiting the use of holdback for replacement work or payment of claims when a contract or subcontract has been abandoned or terminated. This change ensures that holdback remains protected when a contract ends before completion, regardless of default, abandonment, or termination.

2.3 Lien Rights Do Not Expire Annually

One of the most controversial aspects of Bill 216 was its approach to annual release of holdback and the annual expiry of liens.

Bill 216 provided that liens arising from the supply of services or materials covered by a notice of annual release of holdback would expire 60 days after the notice was published. The owner would then be required to release annual holdback within 14 days from the expiry of the applicable lien period.

Following the publication of Mr. Glaholt’s report and introduction of Bill 216, industry stakeholders raised concerns about tying annual holdback release to annual lien expiry. Particularly, there was widespread concern that the new scheme would force contractors and subcontractors to register liens every year on multi-year projects to protect their rights. Stakeholders warned that this would likely result in an increase of liens claims overall and create unnecessary disruption to projects.

Bill 60 answered industry concerns about annual expiry of liens by providing that lien preservation timelines will continue to operate as under the pre-2026 version of the Construction Act. As a result, lien expiry remains tied to the earliest of:

- The publication of a certificate of substantial performance, completion, abandonment or termination of the contract (for contractor’s liens); or

- The dates listed above, the last day that lienable services or materials were supplied to the improvement, or certification of the subcontract under section 33 (for liens of other persons).

Further, Bill 60 also amends section 26(4) to tie the release of the holdback to the date of publication of the notice of annual release of holdback, rather than the expiry of the lien period on an annual basis.

2.4 Lien Rights for Preconstruction Design Services

The amendments also introduce subsection 14(4) to the Construction Act, which addresses a long-standing issue for consultants and design professionals who supply preconstruction services.

Under the pre-2026 version of the Construction Act, architects, engineers, and other professionals providing preconstruction services could only assert a lien if they supplied services that enhanced the value of the owner's interest in the land. That said, in cases where no physical improvement had yet been made, it was difficult to determine whether such preconstruction work in and of itself enhanced the value of the land. This led to uncertainty both as to whether design professionals had lien rights for certain preconstruction work, and if they did, exactly when those lien rights arose.

A new subsection 14(4) addresses this by creating a presumption that a lien will arise for designs, plans, drawings or specifications for planned improvements where the owner has retained holdback. As a result, professionals providing such preconstruction services to a planned improvement will be deemed to have a lien for the price of those services if the owner retains holdback unless the owner can prove that the services did not enhance the value of the land.

This amendment fills a long-recognized gap in the Construction Act. By tying the deemed lien right to the retention of holdback, the legislation now provides clearer and more reliable protection for pre-construction professionals whose services are integral to construction projects but are often performed before any physical improvement occurs.

3. Prompt Payment and Adjudication

3.1 New “Deeming” Provision – Proper Invoices

Under the pre-2026 version of the Construction Act, prompt payment obligations were triggered only upon the submission of a “proper invoice” that strictly complied with the statutory requirements.

Section 6.1(1) defined a proper invoice as a written bill or other request for payment for services or materials under a contract, provided it contained certain prescribed information.

Because the prompt payment timelines were engaged only upon receipt of an invoice that satisfied these requirements, owners could delay the commencement of a payment cycle by disputing invoices on the basis of technical or minor deficiencies.

Bill 216 introduces a significant change through the addition of subsection 6.1(2). Under this new “deeming” provision, an invoice that does not strictly comply with the requirements of section 6.1(1) will nonetheless be deemed to be a proper invoice unless, within seven days of receiving it, the owner provides written notice to the contractor identifying the alleged deficiency and specifying what is required to remedy it.

Once an invoice is deemed to be a proper invoice, the prompt payment timelines apply. The owner must pay the invoice within 28 days, unless it delivers a notice of non-payment within 14 days. Importantly, the obligation to provide a deficiency notice does not displace the owner’s obligation to issue a notice of non-payment where the amount owing is disputed; both notice requirements may apply concurrently.

The practical effect of the deeming provision is reallocation of administrative responsibility between owners and contractors. Owners are now required to promptly review incoming invoices and raise any deficiencies within the seven-day statutory window. Contractors, in turn, benefit from a statutory presumption that invoices are proper invoices unless timely and specific notice of deficiency is provided.

3.2 Extended Adjudication Period

Under the pre-2026 Construction Act, section 13.5(3) prohibited the commencement of an adjudication if the notice of adjudication was delivered after the contract or subcontract had been “completed”. The provision has since been amended to impose a defined limitation period.

Adjudications in respect of a contract may now be commenced within 90 days after the contract is completed, abandoned, or terminated. For subcontracts, an adjudication must be commenced within 90 days of the earliest of: (i) the date the general contract is completed, abandoned, or terminated; (ii) the date the subcontract is certified as complete under section 33; or (iii) the date the subcontractor last supplied services or materials to the improvement.

As Mr. Glaholt observed in his report, there was broad consensus among consultees that statutory adjudication should remain available to support all payments due under all contracts and subcontracts. This objective could not be achieved so long as the right to adjudicate expired upon contract completion. The extension of the adjudication period is intended to allow sufficient time for holdback release and to enable adjudication to resolve disputes arising from holdback release.

3.3 Extended Scope of Adjudication

The scope of adjudications is now governed by Ontario Regulation 264/25 rather than being explicitly listed in the Act. Additionally, parties may refer disputes to adjudication on any matter agreed to in the contract or prescribed by Regulation.

That change followed the evolution of adjudication in the United Kingdom, where adjudication was introduced as a process for certain limited prescribed matters and over time evolved into a more comprehensive model. That step has now been taken in Ontario, with the original “targeted” adjudication approach making way for a scheme in which parties are free to include whatever they want in an adjudication with the concurrence of the adjudicator.

3.4 Introduction of Private Adjudicators

Until these amendments, adjudications could only be conducted by an adjudicator listed in the registry maintained by ODACC. As outlined in Mr. Glaholt’s report, while that system worked well to allow low-dollar value disputes to be adjudicated at a fair price, thus providing access to justice, it also created an unnecessary limitation on party autonomy.

Section 13.9 of the Construction Act has now been amended to allow for both registry adjudicators and private adjudicators. As per section 21 of Ontario Regulation 264/25, parties may agree to a private adjudicator if:

- There is a written agreement signed by the parties and an adjudicator that discloses the applicable terms and the adjudicator fee to which they have agreed; and

- If the adjudicator fee amounts to an hourly rate of at least $1,000, regardless of how it is charged.

Private adjudicators must still be qualified by ODACC. However, an adjudicator cannot hold both a certificate of qualification as a registry adjudicator and a certificate of qualification as a private adjudicator at the same time, though they may apply to ODACC at any time to exchange one type of certificate for the other.

3.5 Public Adjudication Determinations

To date, the results of adjudications in Ontario have been kept mostly private and confidential. That fact was criticized by the Divisional Court in Caledon (Town) v. 2220742 Ont. Ltd. o/a Bronte Construction, 2024 ONSC 4555 where Justice Corbett noted that:

[A]pparently neither the Merits Decision nor the Jurisdiction Decision have been released to legal databases. They should be the ‘open court principle’ applies to adjudicative bodies and public release of decisions is one way in which decision makers such as ODACC adjudicators are publicly accountable.

That decision was cited with approval in the Glaholt Report.

Going forward, adjudication determinations will be published on ODACC’s website. However, before publication, ODACC must ask each party to the adjudication whether, in the party’s view, the determination should be anonymized, and if any party answers in the affirmative, ODACC must:

- Request that each party indicate, in the time and manner specified, any portions of the determination that, in the party’s view, may identify either of the parties; and

- Ensure that every portion indicated by a party in response to the request does not appear in the published version of the determination.

This provision applies to all adjudications in which the notice of adjudication was given on or after January 1, 2027.

This change was not intended to give adjudication determinations any precedential value. Rather, the Glaholt Report, and presumably the Regulation, reflect the view that the adjudications must be transparent to maintain credibility.

3.6 Costs of an Adjudication

Unlike arbitration or litigation, where the losing party is typically required to pay all or part of the winner’s costs, sections 13.16 and 13.17 of the pre-2026 Construction Act provided that parties to an adjudication must bear their own costs. An exception arose only where the adjudicator determined that a party has acted, in respect of the improvement, in a frivolous, vexatious, abusive, or bad faith manner. In that case, the adjudicator could require the offending party to pay some or all of the other party’s costs.

Mr. Glaholt’s report noted that, during consultation, one consultee identified a potential ambiguity in this provision: does “acted in respect of the improvement” implicitly include conduct “in respect of the adjudication” itself? Mr. Glaholt concluded that there was no rational basis to exclude conduct during the adjudication from the scope of the provision and therefore recommended adding the words “in respect of the adjudication” to section 13.17. That recommendation has been adopted in the amended version of section 13.17.

Practically speaking, the amendment removes any ambiguity. If a party, or its counsel, acts in bad faith or otherwise improperly in the conduct of the adjudication, it may be required to pay some or all of the other party’s costs. This development is noteworthy given the growing concerns about parties unnecessarily increasing the costs of adjudication or delaying determinations by introducing processes more commonly seen in arbitration or litigation, which undermines the efficient and cost-effective resolution of disputes through adjudication.

4. Administrative Amendments

4.1 Defined Publications for Notices and Certificates

The ongoing modernization of the Construction Act has also extended to the mechanisms through which statutory notices are published. The pre-2026 version of the Construction Act required publication in a “construction trade newspaper”. O. Reg. 266/25 replaces that term with the newly defined category of “construction trade news website.” O. Reg. 266/25 expressly designates three platforms that satisfy this definition:

- The Daily Commercial News;

- Link2Build; and

- Ontario Construction News.

By enumerating the acceptable publication platforms, O. Reg. 266/25 eliminates uncertainty regarding compliance and reduces the likelihood of disputes over whether a notice was validly published.

4.2 Joinder of Lien and Trust Claims

The amendments address the procedural relationship between lien claims and breach of trust claims. Ontario Regulation 265/25 introduces a new subsection which confirms that a party may join a lien claim and a breach of trust claim in a single action. This in effect allows parties to advance related claims arising from the same project circumstances within one proceeding, simplifying the litigation process, and reducing the cost and burden associated with parallel actions.

Further, subsection 3(4) of Ontario Regulation 302/18 affirms that motions seeking relief from joinder remain subject to the standard interlocutory motion requirements under rule 5.05 of the Rules of Civil Procedure.

5. Transition Provisions

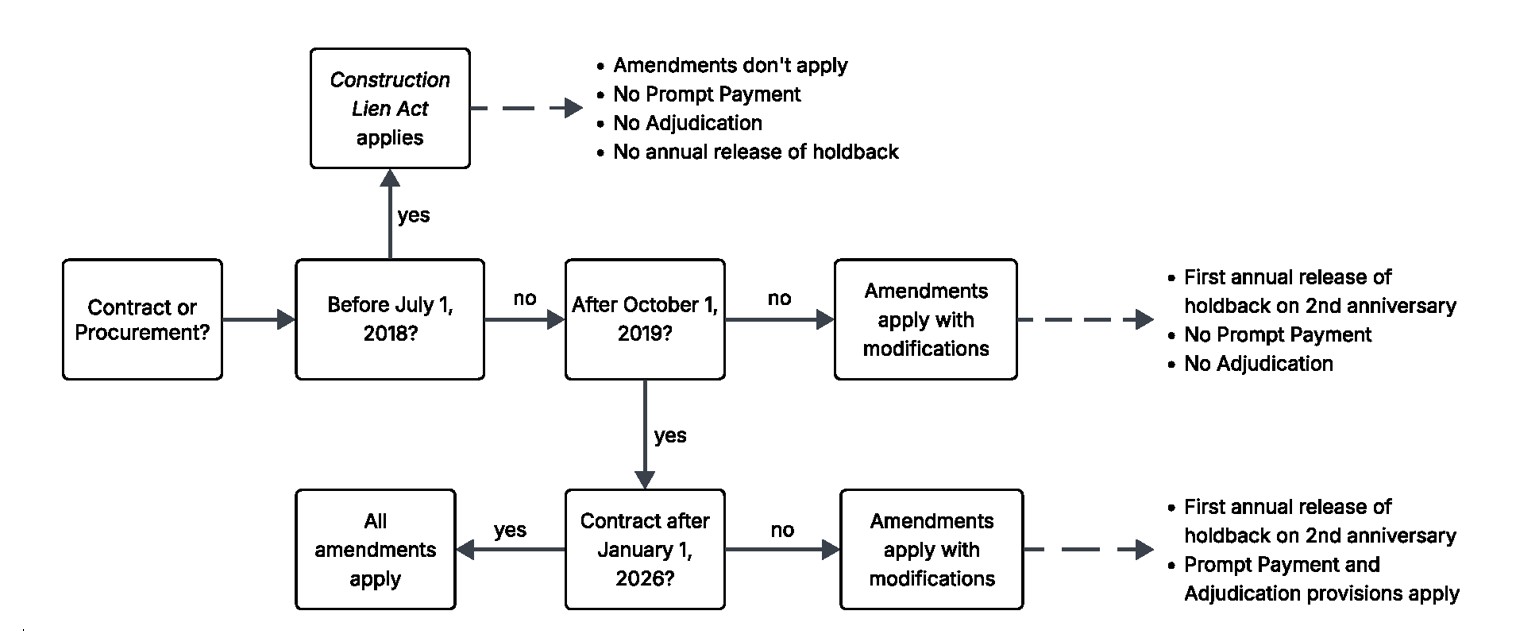

Most of the amendments in Bill 216 and Bill 60 take effect immediately on January 1, 2026, applying to all improvements across Ontario, with some exceptions.

A new section 87.4(4) provides transition provisions relating to the holdback scheme:

- For all new contracts entered after January 1, 2026, mandatory annual holdback release will apply on the first anniversary of the contract without modification.

- For contracts that are effective prior to January 1, 2026, annual release of holdback will begin on the second anniversary of the contract that follows January 1, 2026.

Bill 60 also introduces a specific transition provision for public-private partnership (P3) contracts under section 1.1 of the Construction Act. New section 87.4(5) provides that the version of section 26 in force before January 1, 2026 will continue to apply to all project agreements entered before that date. As a result, P3 project agreements entered prior to January 1, 2026 will not be subject to the new annual holdback release regime.

These new transition provisions do not, however, modify the existing transition rules in section 87.3 of the pre-2026 version of the Construction Act. Consequently, the amendments introduced by Bills 216 and 60 do not apply to improvements where the contract was entered into or the procurement process was commenced on or before June 30, 2018.

For these legacy projects, adjudication remains unavailable, there is no mandatory annual release of holdback, the prompt payment provisions in section 6.1 do not apply, and the former lien preservation and perfection timelines of 45 days for preservation and 45 days for perfection continue to govern.

Below is a visual representation of how this works:[2]

6. Practical Checklist for Stakeholders

A concise, actionable list for navigating the January 1, 2026 amendments:

- For payers: Revise workflows to ensure that invoices from contractors and subcontractors are reviewed promptly upon receipt. This will allow timely issuance of deficiency notices under the new deeming provisions and ensure notices of non-payment are issued where required. Further, update administrative processes to ensure the timely issuance of notices of annual release of holdback and the actual release of holdback funds within the prescribed timelines.

- For design professionals: Consider negotiating contract terms to secure holdback for pre-construction services, thereby protecting lien rights for design work provided before physical improvements are made.

- For counsel: Where appropriate, include claims for breach of trust alongside lien claims to take advantage of the ability to join these claims in a single proceeding under the new regulations.

- For project administrators and accounting teams: Ensure tracking and documentation systems are updated to monitor holdback accruals, notices issued, and payments made, to maintain compliance and facilitate audits if required.

- For legal and compliance teams: Provide training or guidance to internal staff and external partners on the practical implications of the amendments, particularly around holdback release, adjudication, and lien rights.

- For all stakeholders: Update internal workflows to reflect the new adjudication timelines and procedures, including the ability to refer disputes to adjudication within 90 days of contract completion, abandonment, or termination. Further, consider initiating adjudication of holdback disputes promptly once holdback becomes overdue, taking advantage of the mandatory annual release rules and extended adjudication availability. Lastly, review and update standard form contracts, notice provisions, and payment protocols to ensure compliance with the amendments, including proper invoicing requirements, annual holdback release, and prompt payment timelines.

[1] D.W. Glaholt, “The Adjudication Option: The Case for Uniform Payment & Performance Legislation in Canada” (2006), 53 C.L.R. (3d) 8.

[2] Note that this flowchart does not deal with the transition provisions for public-private partnership (P3) contracts under section 1.1 of the Construction Act.